Rail Baltica Growth Corridor kick-off conference

Helsinki, 9 June, 2011

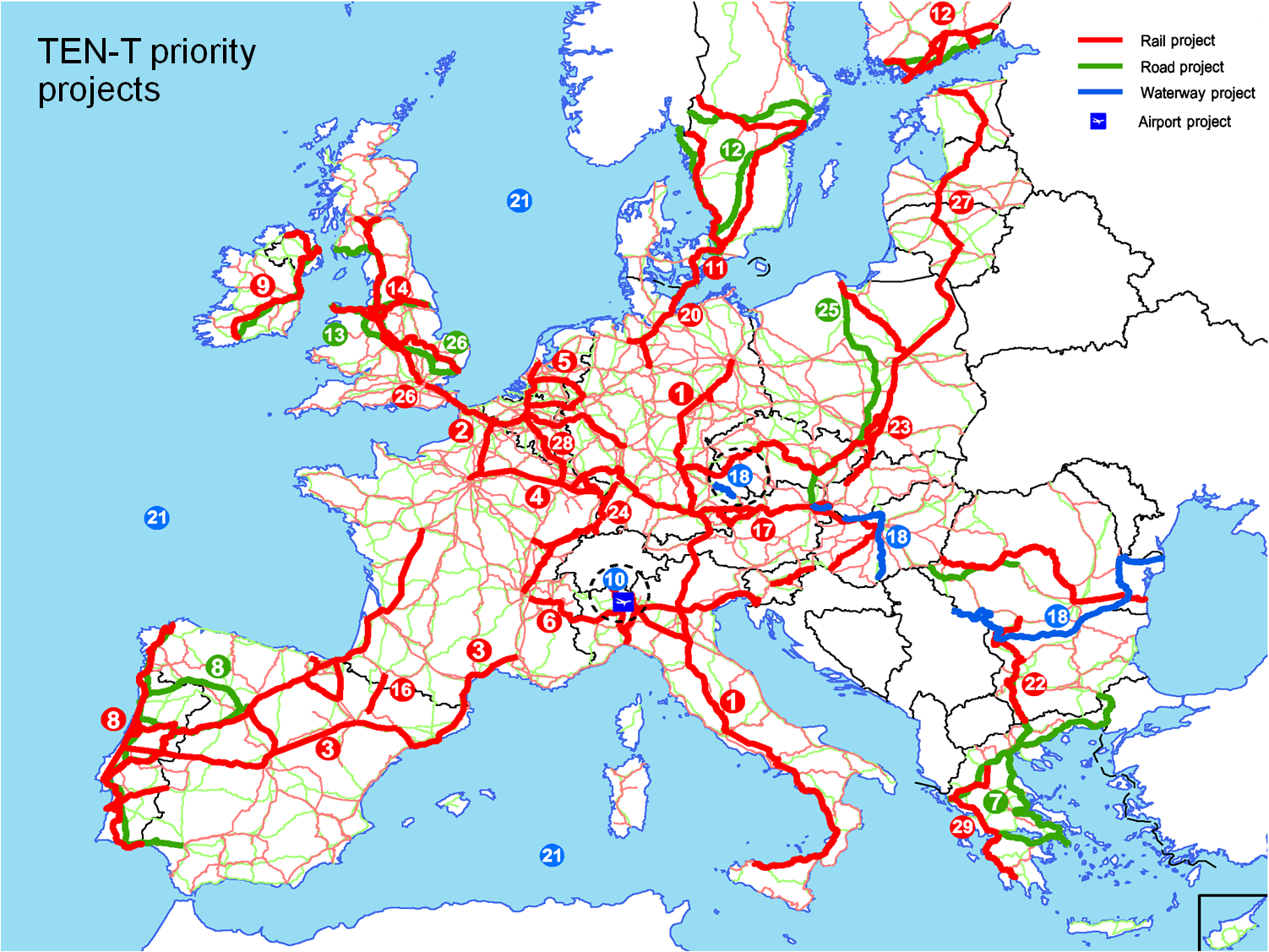

The title of today’s conference points to discussion about a concrete project – “Rail Baltica” (priority project No. 27 of the Trans-European Transport Network) – but also to much broader issues: growth related to transport connections, and discussions about the larger picture concerning transport infrastructure development in Europe and in neighbouring areas.

Rail Baltica is one project to improve north–south connections among European Union Member States: Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. Everybody admits that land connections between these Member States and the centre and south of Europe are very poor. International passenger connections are poor because roads are still of bad quality, rail services slow and infrequent, and there is no direct passenger railway line from Tallinn to Warsaw at all. For freight there is a developed east–west network but not a comparable north–south network. The lack of passenger rail service has led to the development of a reasonable quality coach network offering both internal and international services which are very popular, but still used mostly for the shorter distances within one country and between two neighboring countries.

Rail Baltica is one possibility to improve these connections. In addition, we should not forget about developing road connections as well. The once very popular Via Baltica project has now disappeared from high-level plans.

Recently a feasibility study was completed analyzing a more radical option: a faster railway with European gauge – 1435 mm – between Tallinn and Marijampole via Riga and Kaunas. The study shows that there are route options that can be considered economically and financially viable. However, financial analyses also show that EU co-funding (of around €2.5 billion) is essential. Please note: the total cost (not discounted) is estimated to be €3.7 billion. The question is: do we need the improvement of land transport infrastructure for north-south connections of the Baltic countries and Finland at all?

Today’s conference will elaborate on these issues and I presume there are many clear presentations which will show how transport connections facilitate economic growth in regions linked to transport corridors – in general and between Baltic countries, Finland, Poland and their regions in particular.

The main trading partners for the Baltic countries are European Union Member States. 75% of Estonia’s and Latvia’s total trade is inside the EU-27; for Lithuania and Finland intra-EU trade amounts to about 60% of total trade. Statistical analysis shows that there is a very strong correlation between GDP growth and freight growth and especially for destinations between the Baltic States, Finland and Germany. Thus, as our economies grow, it is correct to assume that trade and freight levels grow as well.

More and more people travel from Finland and Baltic countries to the rest of Europe. For example, in 2009 Finns made a total of 5.6 million leisure trips abroad, compared to about 4 million in 2000 – this is about 40% more. Estonians made 752 000 overnight trips abroad in 2009 (which is 75 000 more than in 2007). As the income in the region grows, it is logical to assume that, as in the past, the number of trips will also continue to increase. Statistics also show that neighbouring countries and EU countries are visited the most. Based on this data, we can also assume that, in the future, the use of transport infrastructure in the north–south corridor will increase and the need to develop this infrastructure will become more and more acute.

What role should the north–south corridor play among other transport infrastructure priorities in Finland and the Baltics? Clearly, seaports play a very important role in our countries. All have made substantial investments in ports. They will play an important role in the future. The airports are strategically immensely sensitive and important. Modern infrastructure must be a flexible network of smooth chains. Freight transport will become increasingly a multimodal business managed by logistics companies. Railways and roads must have good connections to airports and seaports. In the north–south corridor this aspect must be further developed.

At the moment most freight is transported by road, by sea and in the air. This points to the lack of a rail freight corridor. Due to the higher proportion of road and sea freight prices related to labour and fuel, it is likely that in the coming years, prices for these modes will rise faster than for rail freight, meaning that the latter will become increasingly competitive. Passenger railways are rapidly developing in Europe and China, and the United States has plans to make substantial efforts to develop modern passenger railways.

What is the impact of Baltic north–south connections on relations with third countries, first of all – with Russia? We have a controversial picture here. Some people consider the Rail Baltica project as a something opposed to Russian interests in the Baltics. Today that is ridiculous. The historical truth is that in Soviet times all direct connections between Baltic countries were strongly discouraged: everything had to happen only via Moscow. Transport routes were developed first in east–west directions. Maybe some individuals still think in the same manner today. If that is the case, we really must oppose such an attitude.

Second, opposition to the development of Rail Baltica and the north–south corridor in general comes from a thinking which is quite widespread but not very openly discussed and not very vocally expressed – but according to which Rail Baltica and the north–south corridor would be irrelevant in an economic sense: the real benefits can come only from east–west corridors. First of all, let us discuss this in an open and frank manner. Nobody is against the development of transport flows in east–west corridors; on the contrary, what can we have against Russian tourists using good roads and comfortable passenger trains and bringing money to our countries? Nobody can be against the revenues and jobs brought by east–west freight transport.

One big issue is the difference in railway gauges in the European transport area and Russia. This cannot be a question of identity or political priority. If we want to develop rail transport and make it competitive vis-à-vis road transport we must analyse this problem in a rational and pragmatic manner based on technological expertise. The reality today is that there is no commercially successful technology to change the gauge from one size to another. Spain, which has problems with different gauges but has advanced technology to change the gauges, has opted to build new railways to the European gauge: 1435 mm.

Rail passenger traffic between Russia, Finland and the Baltic States has great prospects. The “Allegro” train between St. Petersburg and Helsinki has been a big success. Trains connecting Moscow and St. Petersburg with Riga and Tallinn based on similar principles also have a good economic outlook.

Historically the biggest benefits for Baltic transport enterprises came when Russia extensively used Baltic ports for the export of oil and raw materials. Today Russia has developed its own port infrastructure and directs the main transport flows there.

Beliefs and emotions surround the prospect of container transport between China and Europe. There is no doubt that transport of containers will increase. Last year container traffic to the EU (mainly from Asia) increased by more than 10%. The big container ports of Antwerp, Rotterdam and Hamburg are becoming increasingly saturated and congested, and containers are looking for new ports. Baltic ports fit very well if only there were a reliable rail connection for bringing containers to central and western Europe. The European Union already supports diversification of transport routes between southeast Asia and Europe. We have declared our support and possible assistance to the Russian modernisation project “Transsib 7 days”. Deutsche Bahn has already run an experimental train from Asia to Europe via Russia. But the big volumes will remain on ships.

The development of good transport economic relations between Russia and Europe is harmed by an uncertain economic environment, in which political interference is influencing contracts and pricing in Russia.

Our new plan for the future core TEN-T network is built on connecting important nodes. These nodes are defined as capitals, ports, airports and border crossing points. This principle provides Member States with the tools they need to develop a harmonious network of railways, roads, airports and seaways with clear European value. We now have a great opportunity to create and develop a smooth network of land transport infrastructure in the Baltic region which includes the north–south corridor and east–west corridors in a mutually beneficial way. To make this vision a reality we need the political commitment of governments – and its realisation in concrete decisions, projects, and efficient implementation. We need money and people.

With transport infrastructure planning it is extremely important to underline that transport decisions are always long-term decisions. An airplane flies for 25 years; a train is used for 30 years or more; construction of roads, bridges, ports and railways is done for decades. It means that elections should not change basic infrastructure policies. Governments must have rules and practices enabling them to make such long-term decisions. The absence of a culture of long-term decision making is a major weakness in many European countries.

We need money for our projects. I would like the next budget being planned for the European Union to include significant amounts for the TEN-T network. The current multi-annual financial framework (MAFF) has €8 billion in centralised funding and 43 billion in structural funds. The next MAFF is under discussion and so it’s too early to talk about concrete amounts that could be made available for transport. We all need to make efforts to ensure that sufficient EU funding for transport will remain available by the end of the negotiation processes. But the transport financing model will remain broadly similar to today – there will be funds from the EU centralised transport budget, in addition to money from the cohesion and structural funds, from national budgets of the Member States, the EIB, EBRD and other multilateral banks and from the private sector. The success of a project depends heavily on political commitment, the quality of a project preparation and the right combination of various funding sources.

To involve more private money we need to follow certain principles:

- more private ownership,

- no political interference,

- an independent regulator,

- long term planning,

- a clear revenue stream,

- state aid during launch period.

To develop the north–south corridor in the Baltic countries we need more intensive collaboration between relevant governments, the private sector, regions (cities which can benefit from the development of transport corridors), investment banks and the European Commission. One project coordinator who has done a good job is not enough. We need to establish a permanent collaboration mechanism, a platform or task force which brings all relevant individuals together and works regularly to overcome difficulties. The basis for the functioning of such a platform should be an agreed memorandum of understanding. We are working towards ensuring that such project implementation principles are more frequently used in the next MAFF.

I call on Finnish business and government also to play an active part in developing north–south land connections to central Europe.

Thank you for your attention.

Source – European Commission.

No responses yet